圖書内容

窮畫家瓊珊得了重病,在病房裡看着窗外對面樹上的常春藤葉子不斷被風吹落,她認為最後一片葉子的凋謝代表自己的死亡,于是她失去了生存的意志。醫生認為再這樣下去瓊珊會死去。貝爾曼,一個偉大的畫家,在聽完蘇艾講述室友瓊珊的事情後,夜裡冒着暴雨,用心靈的畫筆畫出了一片“永不凋落”的常春藤葉,讓瓊珊重拾對生命的希望,而自己卻因此患上肺炎,去世了。作品特點《最後的常春藤葉》講述了老畫家貝爾曼為了鼓勵貧病交加的青年畫家頑強地活下去,在風雨之夜掙紮着往牆上畫了一片永不凋零的常春藤葉。他為繪制這傑作付出了生命的代價,但青年畫家卻因此獲得勇氣而活了下來。歌頌了藝術家之間相濡以沫的友誼和蒼涼人生中那種崇高的藝術家品格——舍己救人。

這篇小說,表面上看像一泓靜靜的秋水,水面上卻拂過一絲透骨的寒意。讀着它,就像乘着一葉小舟從秋水上劃過。但是,當我們棄舟上岸,再來顧盼這秋水時,才發現在它的底層,奔湧着一股股洶湧的波濤,這濤聲撞擊着你的心弦,拍打着你的肺腑。貝爾曼,這位在美術園地辛勤耕耘了四十載卻一無所獲的老藝術家,憑着他博大的愛心,用他的生命為代價,完成了一幅不朽的傑作。

創作背景

歐·亨利在大概十年的時間内創作了短篇小說共有300多篇,收入《白菜與國王》(1904)[其唯一一部長篇,作者通過四五條并行的線索,試圖描繪出一幅廣闊的畫面,在寫法上有它的别緻之處。不過從另一方面看,小說章與章之間的内在聯系不夠緊密,各有獨立的内容]、《四百萬》(1906)、《西部之心》(1907)、《市聲》(1908)、《滾石》(1913)等集子,其中以描寫紐約曼哈頓市民生活的作品為最著名。他把那兒的街道、小飯館、破舊的公寓的氣氛渲染得十分逼真,故有“曼哈頓的桂冠詩人”之稱。他曾以騙子的生活為題材,寫了不少短篇小說。作者企圖表明道貌岸然的上流社會裡,有不少人就是高級的騙子,成功的騙子。歐·亨利對社會與人生的觀察和分析并不深刻,有些作品比較淺薄,但他一生困頓,常與失意落魄的小人物同甘共苦,又能以别出心裁的藝術手法表現他們複雜的感情。他的作品構思新穎,語言诙諧,結局常常出人意外;又因描寫了衆多的人物,富于生活情趣,被譽為“美國生活的幽默百科全書”。因此,他最出色的短篇小說如《愛的犧牲》(A Service of Love)、《警察與贊美詩》(The Cop and the Anthem)、《帶家具出租的房間》(The Furnished Room)、《麥琪的禮物》(The Gift of the Magi)、《最後的常春藤葉》(The Last Leaf)等都可列入世界優秀短篇小說之中。

他的文字生動活潑,善于利用雙關語、訛音、諧音和舊典新意,妙趣橫生,被喻為[含淚的微笑]。他還以準确的細節描寫,制造與再現氣氛,特别是大都會夜生活的氣氛。

歐·亨利還以擅長結尾聞名遐迩,美國文學界稱之為“歐·亨利式的結尾”他善于戲劇性地設計情節,埋下伏筆,作好鋪墊,勾勒矛盾,最後在結尾處突然讓人物的心理情境發生出人意料的變化,或使主人公命運陡然逆轉,使讀者感到豁然開朗,柳暗花明,既在意料之外,又在情理之中,不禁拍案稱奇,從而造成獨特的藝術魅力。有一種被稱為“含淚的微笑”的獨特藝術風格。歐·亨利把小說的靈魂全都凝聚在結尾部分,讓讀者在前的似乎是平淡無奇的而又是诙諧風趣的娓娓動聽的描述中,不知不覺地進入作者精心設置的迷宮,直到最後,忽如電光一閃,才照亮了先前隐藏着的一切,仿佛在和讀者捉迷藏,或者在玩弄障眼法,給讀者最後一個驚喜。在歐·亨利之前,其他短篇小說家也已經這樣嘗試過這種出乎意料的結局。但是歐·亨利對此運用得更為經常,更為自然,也更為純熟老到。

正文

在華盛頓廣場西面的一個小區裡,街道仿佛發了狂似地,分成了許多叫做“巷子”的小胡同。這些“巷子”形成許多奇特的角度和曲線。一條街本身往往交叉一兩回。有一次,一個藝術家發現這條街有它可貴之處。如果一個商人去收顔料、紙張和畫布的賬款,在這條街上轉彎抹角、大兜圈子的時候,突然碰上一文錢也沒收到,空手而回的他自己,那才有意思呢!

因此,搞藝術的人不久都到這個古色天香的格林威治村來了。他們逛來逛去,尋找朝北的窗戶,18世紀的三角牆,荷蘭式的閣樓,以及低廉的房租。接着,他們又從六馬路買來了一些錫蠟杯子和一兩隻烘鍋,組成了一個“藝術區”。

蘇艾和瓊珊在一座矮墩墩的三層磚屋的頂樓設立了她們的畫室。“瓊珊”是瓊娜的昵稱。兩人一個是從緬因州來的;另一個的家鄉是加利福尼亞州。她們是在八馬路上一家“德爾蒙尼戈飯館”裡吃客飯時碰到的,彼此一談,發現她們對于藝術、飲食、衣着的口味十分相投,結果便聯合租下那間畫室。

那是五月間的事。到了十一月,一個冷酷無情,肉眼看不見,醫生管他叫“肺炎”的不速之客,在藝術區裡潛蹑着,用他的冰冷的手指這兒碰碰那兒摸摸。在廣場的東面,這個壞家夥明目張膽地走動着,每闖一次禍,受害的人總有幾十個。但是,在這錯綜複雜,狹窄而苔藓遍地的“巷子”裡,他的腳步卻放慢了。

“肺炎先生”并不是你們所謂的扶弱濟困的老紳士。一個弱小的女人,已經被加利福尼亞的西風吹得沒有什麼血色了,當然經不起那個有着紅拳關,氣籲籲的老家夥的常識。但他竟然打擊了瓊珊;她躺在那張漆過的鐵床上,一動也不動,望着荷蘭式小窗外對面磚屋的牆壁。

一天早晨,那位忙碌的醫生揚揚他那蓬松的灰眉毛,招呼蘇艾到過道上去。

“依我看,她的病隻有一成希望。”他說,一面把體溫表裡的水銀甩下去。“那一成希望在于她自己要不要活下去。人們不想活,情願照顧殡儀館的生意,這種精神狀态使醫藥一籌莫展。你的這位小姐滿肚子以為自己不會好了。她有什麼心事嗎?”

“她——她希望有一天能去畫那不勒斯海灣。”蘇艾說。

“繪畫?——别扯淡了!她心裡有沒有值得想兩次的事情——比如說,男人?”

“男人?”蘇艾像吹小口琴似地哼了一聲說,“難道男人值得——别說啦,不,大夫;根本沒有那種事。”

“那麼,一定是身體虛弱的關系。”醫生說,“我一定盡我所知,用科學所能達到的一切方法來治療她。可是每逢我的病人開始盤算有多麼輛馬車送他出殡的時候,我就得把醫藥的治療力量減去百分之五十。要是你能使她對冬季大衣的袖子式樣發生興趣,提出一個總是,我就可以保證,她恢複的機會準能從十分之一提高到五分之一。”

醫生離去之後,蘇艾到工作室裡哭了一聲,把一張日本紙餐巾擦得一團糟。然後,她拿起畫闆,吹着拉格泰姆音樂調子,昂首闊步地走進瓊珊的房間。

瓊珊躺在被窩裡,臉朝着窗口,一點兒動靜也沒有。蘇艾以為她睡着了,趕緊停止吹口哨。

她架起畫闆,開始替雜志畫一幅短篇小說的鋼筆畫插圖。青年畫家不得不以雜志小說的插圖來鋪平通向藝術的道路,而這些小說則是青年作家為了鋪平文學道路而創作的。

蘇艾正為小說裡的主角,一個愛達荷州的牧人,畫上一條在馬匹展覽會裡穿的漂亮的馬褲和一片單眼鏡,忽然聽到一個微弱的聲音重複了幾遍。她趕緊走到床邊。

瓊珊的眼睛睜得大大的。她望着窗外,在計數——倒數上來。

“十二,”她說,過了一會兒,又說“十一”;接着是“十”、“九”;再接着是幾乎連在一起的“八”和“七”。

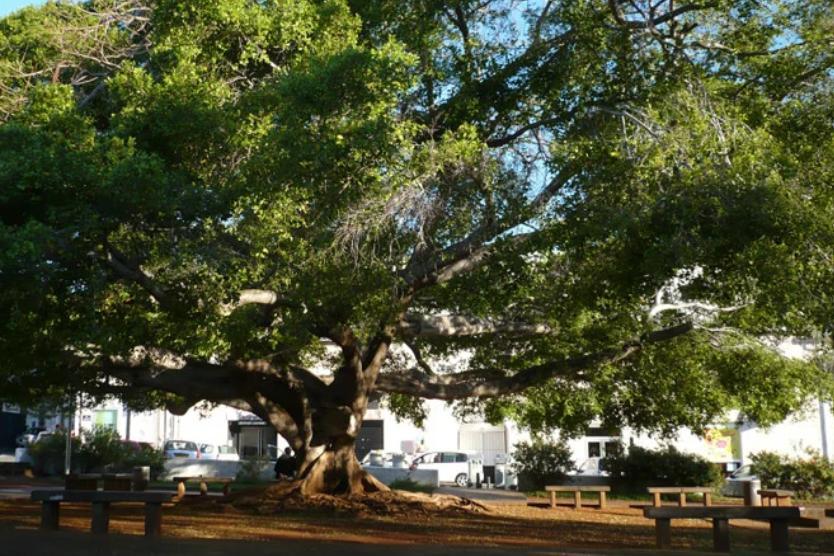

蘇艾關切地向窗外望去。有什麼可數的呢?外面見到的隻是一個空蕩蕩、陰沉沉的院子,和二十英尺外的一幛磚屋的牆壁。一标極老極老的常春藤,糾結的根已經枯萎,樊在半牆上。秋季的寒風把藤上的葉子差不多全吹落了,隻剩下幾根幾乎是光秃秃的藤枝依附在那堵松動殘缺的磚牆上。

“怎麼回事,親愛的?”蘇艾問道。

“六。”瓊珊說,聲音低得像是耳語,“它們現在掉得快些了。三天前差不多有一百片。數得我頭昏眼花。現在可容易了。喏,又掉了一片。隻剩下五片了。”

“五片什麼,親愛的?告訴你的蘇艾。”

“葉子,常春藤上的葉子。等最後一片掉落下來,我也得去了。三天前我就知道了。難道大夫沒有告訴你嗎?”

“喲,我從沒聽到這樣荒唐的話。”蘇艾裝出滿不在乎的樣子數落地說,“老藤葉同你的病有什麼相幹?你一向很喜歡那株常春藤,得啦,你這淘氣的姑娘。别發傻啦。我倒忘了,大夫今天早晨告訴你,你很快康複的機會是——讓我想想,他是怎麼說的——他說你好的希望是十比一!喲,那幾乎跟我們在紐約搭街車或者走過一幛新房子的工地一樣,碰到意外的時候很少。現在喝一點兒湯吧。讓蘇艾繼續畫圖,好賣給編輯先生,換了錢給她的病孩子買點兒紅葡萄酒,也買些豬排填填她自己的饞嘴。”

“你不用再買什麼酒啦。”瓊珊說,仍然凝視着窗外,“又掉了一片。不,我不要喝湯。隻剩四片了。我希望在天黑之前看到最後的藤葉飄下來。那時候我也該去了。”

“瓊珊,親愛的,”蘇艾彎着身子對她說,“你能不能答應我,在我畫完之前,别睜開眼睛,别瞧窗外?那些圖畫我明天得交。我需要光線,不然我早就把窗簾拉下來了。”

“你不能到另一間屋子裡去畫嗎?”瓊珊冷冷地問道。

“我要呆在這兒,跟你在一起。”蘇艾說,“而且我不喜歡你老盯着那些莫名其妙的藤葉。”

“你一畫完就告訴我。”瓊珊閉上眼睛說,她臉色慘白,靜靜地躺着,活像一尊倒塌下來的塑像,“因為我要看那最後的藤葉掉下來。我等得不耐煩了。也想得不耐煩了。我想擺脫一切,像一片可憐的、厭倦的藤葉,悠悠地往下飄,往下飄。”

“你争取睡一會兒。”蘇艾說,“我要去叫貝爾曼上來,替我做那個隐居的老礦工的模特兒。我去不了一分種。在我回來之前,千萬别動。”

老貝爾曼是住在樓下底層的一個畫家。他年紀六十開外,有一把像米開朗琪羅的摩西雕像上的胡子,從薩蒂爾似的腦袋上順着小鬼般的身體卷垂下來。貝爾曼在藝術界是個失意的人。他耍了四十年的畫筆,還是同藝術女神隔有相當距離,連她的長袍的邊緣都沒有摸到。他老是說就要畫一幅傑作,可是始終沒有動手。除了偶爾塗抹了一些商業畫或廣告畫之外,幾年沒有畫過什麼。他替“藝術區”裡那些雇不起職業模特兒的青年藝術家充當模特兒,掙幾個小錢,他喝杜松子酒總是過量,老是唠唠叨叨地談着他未來的傑作。此外,他還是個暴躁的小老頭兒,極端瞧不起别人的溫情,卻認為自己是保護樓上兩個青年藝術家的看家兇狗。

蘇艾在樓下那間燈光黯淡的小屋子裡找到了酒氣撲人的貝爾曼。角落裡的畫架上繃着一幅空白的畫布,它在那兒靜候傑作的落筆,已經有了二十五年。她把瓊珊的想法告訴了他,又說她多麼擔心,惟恐那個虛弱得像枯葉一般的瓊 珊抓不住她同世界的微弱牽連,真會撒手去世。

老貝爾曼的充血的眼睛老是迎風流淚,他對這種白癡般的想法大不以為然,連諷帶刺地咆哮了一陣子。

“什麼話!”他嚷道,“難道世界上竟有這種傻子,因為可惡的藤葉落掉而想死?我活了一輩子也沒有聽到過這種怪事。不,我沒有心思替你當那無聊的隐士模特兒。你怎麼能讓她腦袋裡有這種傻念頭呢?唉,可憐的小瓊珊小姐。”

“她病得很厲害,很虛弱,”蘇艾說,“高燒燒得她疑神疑鬼,滿腦袋都是希奇古怪的念頭。好嗎,貝爾曼先生,既然你不願意替我當模特兒,我也不勉強了。我認得你這個可惡的老——老貧嘴。”

“你真女人氣!”貝爾曼嚷道,“誰說我不願意?走吧。我跟你一起去。我已經說了半天,願意替你替你效勞。天哪!像瓊珊小姐那樣好的人實在不應該在這種地方害病。總有一天,我要畫一幅傑作,那麼我們都可以離開這裡啦。天哪!是啊。”

他們上樓時,瓊珊已經睡着了。蘇艾把窗簾拉到窗檻上,做手勢讓貝爾曼到另一間屋子裡去。他們在那兒擔心地瞥着窗外的常春藤。接着,他們默默無言地對瞅了一會兒。寒雨夾着雪花下個不停。貝爾曼穿着一件藍色的舊襯衫,坐在一翻轉過身的權棄岩石的鐵鍋上,扮作隐居的礦工。

第二天早晨,蘇艾睡了一個小時醒來的時候,看到瓊珊睜着無神的眼睛,凝視着放下末的綠窗簾。

“把窗簾拉上去,我要看。”她用微弱的聲音命令着。

蘇艾困倦地照着做了。

可是,看那!經過了漫漫長夜的風吹雨打,仍舊有一片常春藤的葉子貼在牆上。它是藤上最後的一片了。靠近葉柄的顔色還是深綠的,但那鋸齒形的邊緣已染上了枯敗的黃色,它傲然挂在離地面二十來英尺的一根藤枝上面。

“那是最後的一片葉子。”瓊珊說,“我以為昨夜它一定會掉落的。我聽到刮風的聲音。它今天會脫落的,同時我也要死了。”

“哎呀,哎呀!”蘇艾把她困倦的臉湊到枕邊說,“如果你不為自己着想,也得替我想想呀。我可怎麼辦呢?”

但是瓊珊沒有回答。一個準備走上神秘遙遠的死亡道路的心靈,是全世界最寂寞、最悲哀的了。當她與塵世和友情之間的聯系一片片地脫離時,那個玄想似乎更有力地掌握了她。

那一天總算熬了過去。黃昏時,她們看到牆上那片孤零零的藤葉仍舊依附在莖上。随夜晚同來的北風的怒号,雨點不住地打在窗上,從荷蘭式的低屋檐上傾瀉下來。

天色剛明的時候,狠心的瓊珊又吩咐把窗簾拉上去。

那片常春藤葉仍在牆上。

瓊珊躺着對它看了很久。然後她喊喊蘇艾,蘇艾正在煤卸爐上攪動給瓊珊喝的雞湯。

“我真是一個壞姑娘,蘇艾,”瓊珊說,“冥冥中有什麼使那最後的一片葉子不掉下來,啟示了我過去是多麼邪惡。不想活下去是個罪惡。現在請你拿些湯來,再弄一點摻葡萄酒的牛奶,再——等一下;先拿一面小鏡子給我,用枕頭替我墊墊高,我想坐起來看你煮東西。”

一小時後,她說:

“蘇艾,我希望有朝一日能去那不勒斯海灣寫生。”

下午,醫生來,他離去時,蘇艾找了個借口,跑到過道上。

“好的希望有了五成。”醫生抓住蘇艾瘦小的、顫抖的手說,“隻要好好護理,你會勝利。現在我得去樓下看看另一個病人。他姓貝爾曼——據我所知,也是搞藝術的。也是肺炎。他上了年紀,身體虛弱,病勢來得很猛。他可沒有希望了,不過今天還是要把他送進醫院,讓他舒服些。”

第二天,醫生對蘇說:“她已經脫離危險,你成功了。現在,你隻需要好好護理,給她足夠的營養就行了。”

那天下午,蘇艾跑到床邊,瓊珊靠在那兒,心滿意足地在織一條毫無用處的深藍色戶巾,蘇艾連枕頭把她一把抱住。

“我有些話要告訴你,小東西。”她說,“貝爾曼在醫院裡去世了。他害肺炎,隻病了兩天。頭天早上,看門人在樓下的房間裡發現他難過得要命。他的鞋子和衣服都濕透了,冰涼冰涼的。他們想不出,在那種凄風苦雨的的夜裡,他究竟是到什麼地方去了。後來,他們找到了一盞還燃着的燈籠,一把從原來地方挪動過的梯子,還有幾去散落的的畫筆,一塊調色闆,上面和了綠色和黃色的顔料,末了——看看窗外,親愛的,看看牆上最後的一片葉子。你不是覺得納悶,它為什麼在風中不飄不動嗎?啊,親愛的,那是貝爾曼的傑作——那晚最後的一片葉子掉落時,他畫在牆上的。”

英文原文

In a little district west of Washington Square the streets have run crazy and broken themselves into small strips called "places." These "places" make strange angles and curves. One Street crosses itself a time or two. An artist once discovered a valuable possibility in this street. Suppose a collector with a bill for paints, paper and canvas should, in traversing this route, suddenly meet himself coming back, without a cent having been paid on account!

So, to quaint old Greenwich Village the art people soon came prowling, hunting for north windows and eighteenth-century gables and Dutch attics and low rents. Then they imported some pewter mugs and a chafing dish or two from Sixth Avenue, and became a "colony."

At the top of a squatty, three-story brick Sue and Johnsy had their studio. "Johnsy" was familiar for Joanna. One was from Maine; the other from California. They had met at the table d'hôte of an Eighth Street "Delmonico's," and found their tastes in art, chicory salad and bishop sleeves so congenial that the joint studio resulted.

That was in May. In November a cold, unseen stranger, whom the doctors called Pneumonia, stalked about the colony, touching one here and there with his icy fingers. Over on the east side this ravager strode boldly, smiting his victims by scores, but his feet trod slowly through the maze of the narrow and moss-grown "places."

Mr. Pneumonia was not what you would call a chivalric old gentleman. A mite of a little woman with blood thinned by California zephyrs was hardly fair game for the red-fisted, short-breathed old duffer. But Johnsy he smote; and she lay, scarcely moving, on her painted iron bedstead, looking through the small Dutch window-panes at the blank side of the next brick house.

One morning the busy doctor invited Sue into the hallway with a shaggy, grey eyebrow.

"She has one chance in - let us say, ten," he said, as he shook down the mercury in his clinical Thermometer. " And that chance is for her to want to live. This way people have of lining-u on the side of the undertaker makes the entire pharmacopoeia look silly. Your little lady has made up her mind that she's not going to get well. Has she anything on her mind?"

"She - she wanted to paint the Bay of Naples some day." said Sue.

"Paint? - bosh! Has she anything on her mind worth thinking twice - a man for instance?"

"A man?" said Sue, with a jew's-harp twang in her voice. "Is a man worth - but, no, doctor; there is nothing of the kind."

"Well, it is the weakness, then," said the doctor. "I will do all that science, so far as it may filter through my efforts, can accomplish. But whenever my patient begins to count the carriages in her funeral procession I subtract 50 per cent from the curative power of medicines. If you will get her to ask one question about the new winter styles in cloak sleeves I will promise you a one-in-five chance for her, instead of one in ten."

After the doctor had gone Sue went into the workroom and cried a Japanese napkin to a pulp. Then she swaggered into Johnsy's room with her drawing board, whistling ragtime.

Johnsy lay, scarcely making a ripple under the bedclothes, with her face toward the window. Sue stopped whistling, thinking she was asleep.

She arranged her board and began a pen-and-ink drawing to illustrate a magazine story. Young artists must pave their way to Art by drawing pictures for magazine stories that young authors write to pave their way to Literature.

As Sue was sketching a pair of elegant horseshow riding trousers and a monocle of the figure of the hero, an Idaho cowboy, she heard a low sound, several times repeated. She went quickly to the bedside.

Johnsy's eyes were open wide. She was looking out the window and counting - counting backward.

"Twelve," she said, and little later "eleven"; and then "ten," and "nine"; and then "eight" and "seven", almost together.

Sue look solicitously out of the window. What was there to count? There was only a bare, dreary yard to be seen, and the blank side of the brick house twenty feet away. An old, old ivy vine, gnarled and decayed at the roots, climbed half way up the brick wall. The cold breath of autumn had stricken its leaves from the vine until its skeleton branches clung, almost bare, to the crumbling bricks.

"What is it, dear?" asked Sue.

"Six," said Johnsy, in almost a whisper. "They're falling faster now. Three days ago there were almost a hundred. It made my head ache to count them. But now it's easy. There goes another one. There are only five left now."

"Five what, dear? Tell your Sudie."

"Leaves. On the ivy vine. When the last one falls I must go, too. I've known that for three days. Didn't the doctor tell you?"

"Oh, I never heard of such nonsense," complained Sue, with magnificent scorn. "What have old ivy leaves to do with your getting well? And you used to love that vine so, you naughty girl. Don't be a goosey. Why, the doctor told me this morning that your chances for getting well real soon were - let's see exactly what he said - he said the chances were ten to one! Why, that's almost as good a chance as we have in New York when we ride on the street cars or walk past a new building. Try to take some broth now, and let Sudie go back to her drawing, so she can sell the editor man with it, and buy port wine for her sick child, and pork chops for her greedy self."

"You needn't get any more wine," said Johnsy, keeping her eyes fixed out the window. "There goes another. No, I don't want any broth. That leaves just four. I want to see the last one fall before it gets dark. Then I'll go, too."

"Johnsy, dear," said Sue, bending over her, "will you promise me to keep your eyes closed, and not look out the window until I am done working? I must hand those drawings in by to-morrow. I need the light, or I would draw the shade down."

"Couldn't you draw in the other room?" asked Johnsy, coldly.

"I'd rather be here by you," said Sue. "Beside, I don't want you to keep looking at those silly ivy leaves."

"Tell me as soon as you have finished," said Johnsy, closing her eyes, and lying white and still as fallen statue, "because I want to see the last one fall. I'm tired of waiting. I'm tired of thinking. I want to turn loose my hold on everything, and go sailing down, down, just like one of those poor, tired leaves."

"Try to sleep," said Sue. "I must call Behrman up to be my model for the old hermit miner. I'll not be gone a minute. Don't try to move 'til I come back."

Old Behrman was a painter who lived on the ground floor beneath them. He was past sixty and had a Michael Angelo's Moses beard curling down from the head of a satyr along with the body of an imp. Behrman was a failure in art. Forty years he had wielded the brush without getting near enough to touch the hem of his Mistress's robe. He had been always about to paint a masterpiece, but had never yet begun it. For several years he had painted nothing except now and then a daub in the line of commerce or advertising. He earned a little by serving as a model to those young artists in the colony who could not pay the price of a professional. He drank gin to excess, and still talked of his coming masterpiece. For the rest he was a fierce little old man, who scoffed terribly at softness in any one, and who regarded himself as especial mastiff-in-waiting to protect the two young artists in the studio above.

Sue found Behrman smelling strongly of juniper berries in his dimly lighted den below. In one corner was a blank canvas on an easel that had been waiting there for twenty-five years to receive the first line of the masterpiece. She told him of Johnsy's fancy, and how she feared she would, indeed, light and fragile as a leaf herself, float away, when her slight hold upon the world grew weaker.

Old Behrman, with his red eyes plainly streaming, shouted his contempt and derision for such idiotic imaginings.

"VASS!" he cried. "Is dere people in de world mit der foolishness to die because leafs dey drop off from a confounded vine? I haf not heard of such a thing. No, I will not bose as a model for your fool hermit-dunderhead. Vy do you allow dot silly pusiness to come in der brain of her? Ach, dot poor leetle Miss Yohnsy."

"She is very ill and weak," said Sue, "and the fever has left her mind morbid and full of strange fancies. Very well, Mr. Behrman, if you do not care to pose for me, you needn't. But I think you are a horrid old - old flibbertigibbet."

"You are just like a woman!" yelled Behrman. "Who said I will not bose? Go on. I come mit you. For half an hour I haf peen trying to say dot I am ready to bose. Gott! dis is not any blace in which one so GOOT as Miss Yohnsy shall lie sick. Some day I vill baint a masterpiece, and ve shall all go away. Gott! yes."

Johnsy was sleeping when they went upstairs. Sue pulled the shade down to the window-sill, and motioned Behrman into the other room. In there they peered out the window fearfully at the ivy vine. Then they looked at each other for a moment without speaking. A persistent, cold rain was falling, mingled with snow. Behrman, in his old blue shirt, took his seat as the hermit miner on an upturned kettle for a rock.

When Sue awoke from an hour's sleep the next morning she found Johnsy with dull, wide-open eyes staring at the drawn green shade.

"Pull it up; I want to see," she ordered, in a whisper.

Wearily Sue obeyed.

But, lo! after the beating rain and fierce gusts of wind that had endured through the livelong night, there yet stood out against the brick wall one ivy leaf. It was the last one on the vine. Still dark green near its stem, with its serrated edges tinted with the yellow of dissolution and decay, it hung bravely from the branch some twenty feet above the ground.

"It is the last one," said Johnsy. "I thought it would surely fall during the night. I heard the wind. It will fall to-day, and I shall die at the same time."

"Dear, dear!" said Sue, leaning her worn face down to the pillow, "think of me, if you won't think of yourself. What would I do?"

But Johnsy did not answer. The lonesomest thing in all the world is a soul when it is making ready to go on its mysterious, far journey. The fancy seemed to possess her more strongly as one by one the ties that bound her to friendship and to earth were loosed.

The day wore away, and even through the twilight they could see the lone ivy leaf clinging to its stem against the wall. And then, with the coming of the night the north wind was again loosed, while the rain still beat against the windows and pattered down from the low Dutch eaves.

When it was light enough Johnsy, the merciless, commanded that the shade be raised.

The ivy leaf was still there.

Johnsy lay for a long time looking at it. And then she called to Sue, who was stirring her chicken broth over the gas stove.

"I've been a Bad Girl, Sudie," said Johnsy. "Something has made that last leaf stay there to show me how wicked I was. It is a sin to want to die. You may bring a me a little broth now, and some milk with a little port in it, and - no; bring me a hand-mirror first, and then pack some pillows about me, and I will sit up and watch you cook."

And hour later she said:

"Sudie, some day I hope to paint the Bay of Naples."

The doctor came in the afternoon, and Sue had an excuse to go into the hallway as he left.

"Even chances," said the doctor, taking Sue's thin, shaking hand in his. "With good nursing you'll win." And now I must see another case I have downstairs. Behrman, his name is - some kind of an artist, I believe. Pneumonia, too. He is an old, weak man, and the attack is acute. There is no hope for him; but he goes to the hospital to-day to be made more comfortable."

The next day the doctor said to Sue: "She's out of danger. You won. Nutrition and care now - that's all."

And that afternoon Sue came to the bed where Johnsy lay, contentedly knitting a very blue and very useless woollen shoulder scarf, and put one arm around her, pillows and all.

"I have something to tell you, white mouse," she said. "Mr. Behrman died of pneumonia to-day in the hospital. He was ill only two days. The janitor found him the morning of the first day in his room downstairs helpless with pain. His shoes and clothing were wet through and icy cold. They couldn't imagine where he had been on such a dreadful night. And then they found a lantern, still lighted, and a ladder that had been dragged from its place, and some scattered brushes, and a palette with green and yellow colours mixed on it, and - look out the window, dear, at the last ivy leaf on the wall. Didn't you wonder why it never fluttered or moved when the wind blew? Ah, darling, it's Behrman's masterpiece - he painted it there the night that the last leaf fell."

作者簡介

歐·亨利(O.Henry) 生卒年代:1862.9.11-1910.6.5 美國著名批判現實主義作家,世界三大短篇小說大師之一。

原名威廉·西德尼·波特(William Sydney Porter),是美國最著名的短篇小說家之一,曾被評論界譽為曼哈頓桂冠散文作家和美國現代短篇小說之父。他出身于美國北卡羅來納州格林斯波羅鎮一個醫師家庭。

他的一生富于傳奇性,當過藥房學徒、牧牛人、會計員、土地局辦事員、新聞記者、銀行出納員。當銀行出納員時,因銀行短缺了一筆現金,為避免審訊,離家流亡中美的洪都拉斯。後因回家探視病危的妻子被捕入獄,并在監獄醫務室任藥劑師。他創作第一部作品的起因是為了給女兒買聖誕禮物,但基于犯人的身份不敢使用真名,乃用一部法國藥典的編者的名字作為筆名。1901年提前獲釋後,遷居紐約,專門從事寫作。

歐·亨利善于描寫美國社會尤其是紐約百姓的生活。他的作品構思新穎,語言诙諧,結局常常出人意外;又因描寫了衆多的人物,富于生活情趣,被譽為“美國生活的幽默百科全書”。代表作有小說集《白菜與國王》、《四百萬》、《命運之路》等。其中一些名篇如《愛的犧牲》、《警察與贊美詩》、《帶家具出租的房間》、《麥琪的禮物》、《最後一片常春藤葉》等使他獲得了世界聲譽。

名句:“這時一種精神上的感慨油然而生,認為人生是由啜泣、抽噎和微笑組成的,而抽噎占了其中絕大部分。”(《歐·亨利短篇小說選》

作品特點

《最後的常春藤葉》是美國作家歐·亨利的一篇著名短篇小說。在這篇小說中,作家講述了老藝術家貝爾曼用生命繪制畢生傑作,點燃别人即将熄滅的生命火花的故事,歌頌了藝術家之間相濡以沫的友誼,特别是老藝術家貝爾曼舍己救人的品德。

小說按情節的開端、發展、高潮、結局可分為四個部分。

第1至11節為開端。故事發生在華盛頓的格林尼治村,一個社會下層藝術家聚居的小區。主人公蘇艾和瓊珊是一對志同道合的年輕畫家,她們租用同一間畫室并在一起生活、工作,随着秋天的到來,一位不速之客———肺炎,開始在“ 藝術區”遊蕩。瓊珊不幸被感染,生命垂危。

第12至36節為發展。哀莫大于心死。盡管好友蘇艾鼓勵瓊珊要有信心戰勝病魔,但是瓊珊都不理睬,隻是癡癡地望着窗外凋零的藤葉。此刻的她,已放棄了主觀上求生的努力,而把生命寄予給随風飄零的樹葉,深信當最後一片葉子掉下時,她也該離開人世了。

第37至50節為高潮。不落的藤葉使瓊珊重又燃起了生的欲望。

第51至55節為結局。瓊珊脫離危險,貝爾曼病逝。揭示葉子不落的謎底。

語篇品讀

華盛頓廣場西南的一個小區,街道仿佛發了狂似的,分成了許多叫做“ 巷子”的小胡同。

『品味』 街道分成許多小胡同,作者說“ 街道仿佛發了狂似的”,風趣的風格,開篇就顯現出來了。

『體會』 這是環境描寫。歐·亨利有一種幽默的方式值得回味。難以想象,在年代上,他距離我們一百年不止,在幽默感的豐富上,他超越了我們一百倍。有一群人,他們拿着歐·亨利的小說,一遍一遍地看,咬着小指頭癡癡地笑,有時笑出眼淚來,他的幽默絕不是快餐式的幽默,分明是一種在想象力上的探索,又是一種對生活哲理的捕捉。

到了十一月,一個冷酷無情、肉眼看不見、醫生管他叫做“ 肺炎”的不速之客,在藝術區裡蹑手蹑腳,用他的冰冷的手指這兒碰碰那兒摸摸。

『品味』 采用幽默、風趣、俏皮、比拟的語言,渲染悲劇的喜劇色彩,讓讀者在俏皮的描寫中醒悟内在莊嚴的思想感情,在生動活潑中給人啟迪。

『體會』 交代了時間線索:十一月。作者用幽默、風趣的語言,十分形象地寫出了肺炎流行的過程和危害。

他喝杜松子酒總是過量,老是唠唠叨叨地談着他未來的傑作。此外,他還是個暴躁的小老頭兒,極端瞧不起别人的溫情,卻認為自己是保護樓上兩個青年藝術家的看家惡狗。

『品味』 正面描寫貝爾曼:性格暴躁,酗酒成性,愛講大話(傑作),牢騷滿腹——— 一個窮困潦倒,消沉失意,好高骛遠,郁郁不得志的失意老畫家。

『體會』 介紹貝爾曼,刻畫貝爾曼的肖像,也充滿俏皮和風趣;就在俏皮之中,一個落寞、潦倒、極有個性又極善良的老頭兒形象,活靈活現地站在我們面前。

老貝爾曼的充血的眼睛老是迎風流淚。他對這種白癡般的想法大不以為然,諷刺地咆哮了一陣子。

『品味』通過語言描寫,說明貝爾曼善良,有同情心,關心他人。

『體會』初見貝爾曼主要是通過外貌描寫告訴我們他是一個郁郁不得志的老畫家。這裡由他的“不以為然”和“ 咆哮”讓我們在人物暴躁的性格和嗜酒成性中,看到了他的善良和同情心。

啊,親愛的,那是貝爾曼的傑作———那晚最後的一片葉子掉落時,他畫在牆上的。

『品味』側面描寫了最後一片葉子是貝爾曼冒雨畫上去的,因此得了肺炎,兩天就去世了。從而人格得到升華:崇高的愛心,自我犧牲精神得到展現。結尾揭示葉子是假的,在前文有幾處伏筆暗藏:(1)其它的葉子都落了,隻有這片葉子經曆兩天的狂風暴雨傲然挺立。(2)“你不是覺得納悶,它為什麼在風中不飄不動嗎?”(3)“ 仍舊有一片常春藤的葉子貼在牆上”的“貼”字。

『體會』一片常春藤葉子。它原本就不是一片葉子,也算不上一幅畫,可它卻超越了葉子和畫的含義:它像一位神醫,治愈了瓊珊的肺炎,給了她生活下去的勇氣和希望;它又像一面鏡子,映照出貝爾曼老人的善良心靈,反射出偉大的舍己為人的精神光芒。比期待了二十五年的傑作更有價值。

評價

如果說貝爾曼是那堵松動殘缺的磚牆,那麼瓊珊就像那依附在上面的藤枝;如果說貝爾曼是那株極老極老的常春藤,那麼瓊珊就是那藤上的一片葉子。小說《最後的常春藤葉》讓人從哀傷中奮起,從悲秋中見到陽春,從黑夜中見到光明,從靈魂中體會到悲怆美。

4、貝爾曼是小說的主人公,作品集中寫他的隻有兩處,試分析這個他是怎樣的人?

初見貝爾曼時,作者通過外貌描寫告訴我們:貝爾曼是一個性格暴躁、酗酒成性、牢騷滿腹、郁郁不得志的老畫家;又通過語言描寫,當他得知瓊珊的病情和“白癡般的想法”後,“諷刺地咆哮了一陣子”,寫出他的善良和同情心。再見貝爾曼時,貝爾曼已經身體虛弱,病了兩天就去世了。貝爾曼是因為冒雨畫最後一片葉子,得了肺炎而去世的。他的崇高愛心、自我犧牲精神由此得到了展現。我們看到了貝爾曼平凡的甚至有點讨厭的外表下有一顆火熱的愛心,雖然窮困潦倒,卻無私關懷、幫助他人,甚至不惜付出生命的代價。作者借此歌頌了窮苦朋友相濡以沫的珍貴友情和普通人的心靈美。

作品賞析

整篇小說,作者對于體現主題的主人公貝爾曼的描寫并不多,大都采用了側面烘托。甚至連最感人的貝爾曼畫葉子的鏡頭都沒寫。但我們仍可以強烈感受到貝爾曼老人火一樣的熱情和舍己為人的精神。而且小說給了我們足夠的想象空間,我們可以想象到,那個風雨交加的夜晚,可憐的老人是怎樣冒雨踉踉跄跄爬到離他二十英尺的地方,顫抖着調拌着黃色和綠色,在牆上施展他從未施展的藝術才能,同時也毫不保留地獻出了生命……

當然,瓊珊的康複僅有貝爾曼為之犧牲的最後一片葉子是不夠的,還需要瓊珊自己的力量來戰勝病魔。在瓊珊患肺炎病危的時刻,醫生為什麼既不判她“ 死刑”,又不肯定她可以治愈,而說一切看她自己呢?就是因為在生與死、抗争與屈服之間,隻有自己樹立信心,作出努力,才能得勝。瓊珊的病果然康複了。每個人都會遇到困難和挫折,關鍵是看你自己有沒有信心,能不能去面對,用自己的力量去克服它。瓊珊也曾陷入失望的低谷,但她在貝爾曼用生命換來的最後一片藤葉的鼓舞下,她重新振作起來,直到康複。她是一位戰勝了困難的勇敢者、勝利者!

綜觀全文,可以看出這篇小說極具思想性,它既沒有驚天動地扣人心弦的情節,也沒有更多的華麗的辭藻。但它以崇高的思想作為整篇小說的支柱,含義深邃。或許這也是歐·亨利的成功之處吧!